Everyone knows entropy exists. Almost nobody can explain it without sounding like a physics textbook or a performative motivational poster.

I named my newsletter "Against Entropy" not because I wanted to sound clever, but because it describes the only work I've ever found worth doing. Before I explain what that means, let me tell you what entropy actually is. Not the hand-wavy version. The real thing.

The Coffee Cup Problem

Pour cream into black coffee. Watch it swirl. Wait thirty seconds.

You now have brown coffee. Uniform. Mixed. And here's the strange part: you will never, not once in the lifetime of the universe, see that brown coffee spontaneously separate back into black coffee and white cream.

Why?

Not because it's impossible. The physics allows it. Every molecule could, in theory, drift back to its original position. The math permits it.

But the math also tells you the odds. The number of ways molecules can arrange themselves into "mixed" vastly outnumbers the ways they can arrange themselves into "separated." We're talking about ratios with more zeros than atoms in the observable universe.

This is entropy. Not "disorder" in some vague sense. A precise mathematical statement: systems naturally evolve toward states that can be achieved in more ways.

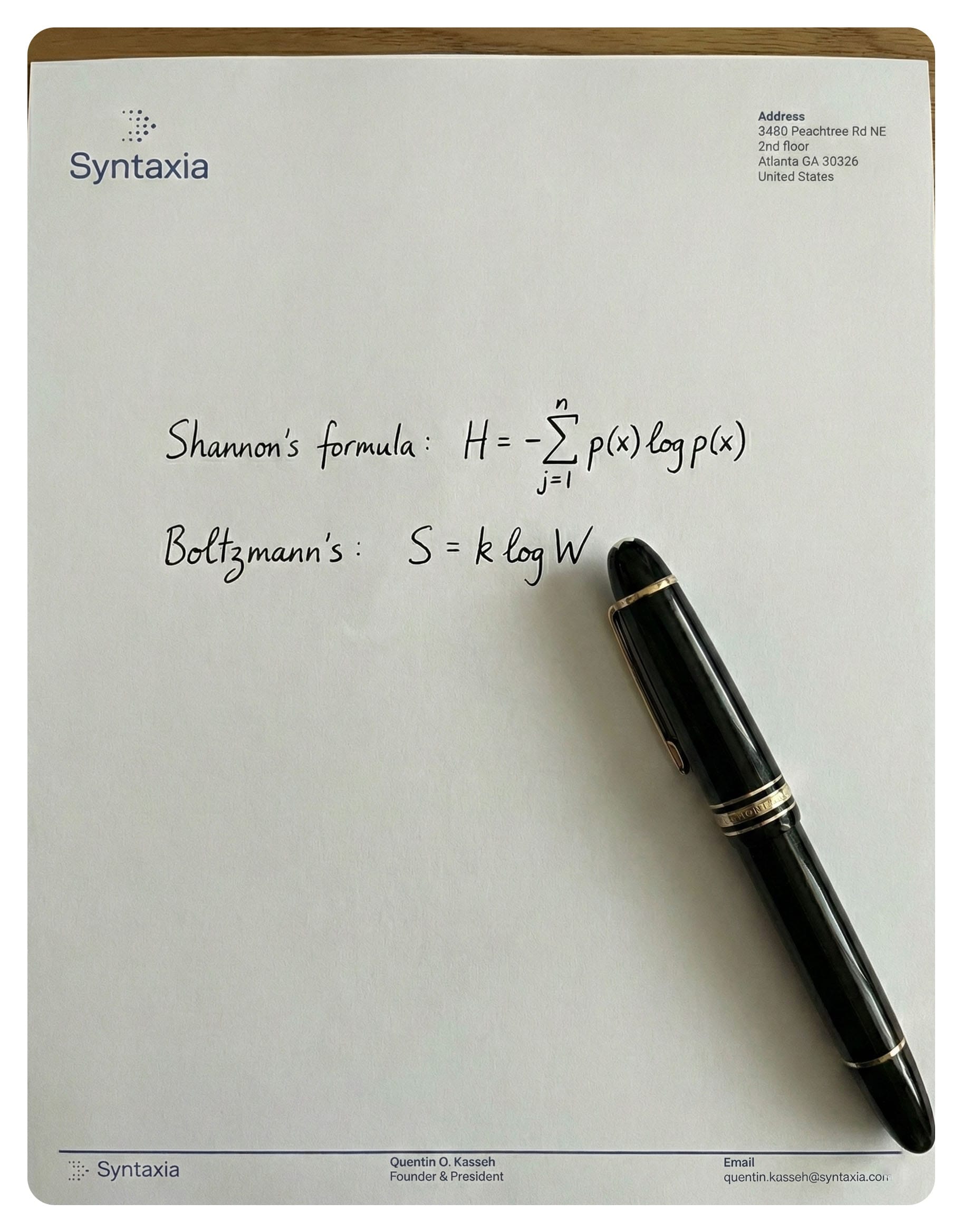

The Austrian physicist Ludwig Boltzmann figured this out in the 1870s and spent the rest of his life defending the idea against colleagues who thought he was insane. He carved the equation into his tombstone. Literally.

Ludwig Boltzmann, who died by his own hand #OTD 1906, is remembered by a tombstone bearing his celebrated equation for entropy. pic.twitter.com/MVwPGeaEQ2

— Brian Greene (@bgreene) September 5, 2018

The relationship between entropy (S) and the number of possible arrangements (W). He died thinking he'd failed to convince anyone. A decade later, everyone agreed he was right.

The Arrow of Time

Here's what makes entropy strange: it's the only law of physics that cares about direction.

Drop a ball. It falls. Play the video backward, and you see a ball rising. Weird, but the physics works both ways. Newton's laws don't care which direction time flows.

But play a video of cream mixing into coffee backward, and anyone watching knows something is wrong. The unmixing looks impossible. Not just unlikely. Wrong.

Entropy is what makes time feel like time. It's why you remember yesterday but not tomorrow. It's why cause precedes effect. It's why buildings crumble but rubble never spontaneously assembles into buildings.

The second law of thermodynamics says entropy in a closed system always increases or stays the same. Never decreases. This is the most fundamental asymmetry in the universe.

Everything runs downhill. Everything diffuses. Everything mixes.

From Physics to Information

In 1948, Claude Shannon (yes, that's really his name) was working at Bell Labs on a seemingly mundane problem:

How do you measure information? If you're sending a message over a telegraph wire, how do you quantify how much "information" you've transmitted?

Shannon realized that information and uncertainty are the same thing. A message carries information precisely to the extent that it resolves uncertainty. If I tell you "the sun rose this morning", I've told you almost nothing. You already knew that. If I tell you "there's a rhinoceros in your kitchen", I've told you a lot. That was unexpected.

Shannon needed a mathematical formula to capture this. He derived one. Then he showed the derivation to John von Neumann, who told him to call it "entropy" because the formula was identical to Boltzmann's thermodynamic entropy.

This wasn't a metaphor. It wasn't poetic license. The mathematics are literally the same.

Information entropy measures the average surprise in a message. High entropy means high uncertainty, lots of possible outcomes, lots of information when you resolve it. Low entropy means predictability, fewer possibilities, less information content.

This connection between physics and information theory is one of the deepest results in twentieth-century science. It suggests that at some fundamental level, thermodynamics and information are the same thing. The universe is running out of surprise.

Entropy and Art

Here's where it gets interesting.

Every artist is fighting entropy. Not metaphorically. Actually.

Think about what a painting is. Canvas and pigment naturally tend toward brown mush. Left alone, colors fade, canvas degrades, meaning dissipates. A painting is a temporary arrangement of matter that imposes order on chaos. It says: "These particular molecules, in this particular arrangement, for this particular moment."

The painter Robert Smithson understood this better than almost anyone. His most famous work, Spiral Jetty, is a 1,500-foot coil of mud and basalt jutting into Utah's Great Salt Lake. He built it knowing it would erode. Knowing the lake would rise and fall, covering and uncovering it. Knowing that entropy would win.

That was the point.

Smithson called his work "entropy made visible." He wasn't fighting entropy. He was collaborating with it, making art that acknowledged its own impermanence.

Music works the same way. A song is a structure imposed on silence. The composer arranges sound waves into patterns that resist the natural tendency toward noise. Then the performance ends, the reverberations fade, and silence returns. Entropy wins again.

Art that pretends to be permanent is lying. Art that acknowledges entropy is telling the truth about the universe.

Entropy in Systems

Now we get to the part that matters for my work.

Every system you've ever built is fighting entropy. Your codebase, your data warehouse, your organization, your documentation. All of them.

Left alone, code degrades. Not because of bugs. Because requirements change and the code doesn't. Because the person who understood the architecture left. Because twelve developers made 12 "quick fixes" and nobody updated the mental model. The code still runs. It just stops making sense.

Left alone, data degrades. I've written about this extensively in The Two Ways Your Data Lies to You. A column called customer_status still contains strings. The pipeline still runs. But six months ago "active" meant "logged in within 30 days" and now it means "has a valid subscription". Same structure. Different meaning. Entropy didn't break your data. It corrupted the relationship between your data and reality.

Left alone, organizations degrade. Tribal knowledge accumulates in people's heads instead of documentation. Processes that made sense in one context persist long after the context changed. Teams optimize locally while system-wide coherence erodes. Everyone is busy. Nobody knows why.

The building doesn't collapse. It just becomes uninhabitable. The data doesn't disappear. It just stops being true. The organization doesn't dissolve. It just stops working.

Why "Against Entropy"

So why name a newsletter after this?

Because fighting entropy is the only game worth playing.

I spent time in a military academy years ago. It taught me uncomfortable things about discipline, commitment, and showing up when you don't feel like it. One lesson stuck:

The gap between amateurs and professionals isn't talent. It's maintenance.

Amateurs build things. Professionals maintain them.

Building is the fun part. You start with a blank slate. You impose order on chaos. You see progress every day. Dopamine flows.

Maintaining is the hard part. You fight decay. You update documentation nobody reads. You refactor code that already works. You have the same conversation about data quality for the fifteenth time. Progress is invisible because progress means things didn't get worse.

Most people want to build. Almost nobody wants to maintain. That's why entropy wins so often.

I started Syntaxia because I saw the same pattern everywhere: companies drowning in data that technically exists but practically means nothing. Dashboards that render correctly while telling lies. Metrics that everyone uses and nobody trusts. The data didn't break. It degraded.

Semantic drift is what I call this phenomenon. The silent corruption of meaning. And it happens because organizations don't invest in maintenance. They build pipelines but not governance. They hire analysts but not ontologists. They buy tools but not discipline.

What Fighting Entropy Looks Like

I want to be concrete here.

Fighting entropy in data systems means:

Defining things once and enforcing the definitions everywhere. When "revenue" means five different things in five different dashboards, that's not a technical problem. That's entropy. The solution isn't a better BI tool. It's an ontology: a formal, versioned, governed definition of what "revenue" means, propagated across every system. Dave McComb has been writing about this for years. Almost nobody does it because governance is less fun than building new dashboards.

Maintaining semantic integrity over time. It's not enough to define things correctly on day one. You have to keep them correct on day 365 and day 1,000. This means change management. Versioning. Active stewardship. Boring, essential work.

Investing in knowledge graphs and ontologies. These aren't buzzwords. They're technologies specifically designed to capture and preserve meaning. A relational database stores facts. A knowledge graph stores facts and the relationships between them. That relationship layer is what lets you detect when meanings drift.

Treating documentation as a first-class deliverable. Code without documentation is entropy waiting to happen. Architecture without rationale is entropy waiting to happen. Decisions without context are entropy waiting to happen. Writing things down is maintenance. Maintenance is the work.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Here's the part nobody wants to hear.

You cannot win against entropy. Not permanently. The second law of thermodynamics is the most battle-tested prediction in all of physics. Entropy always increases in the long run.

But "long run" matters.

The sun will burn out in about 5 billion years. That doesn't mean you shouldn't plant a tree. Entropy will eventually claim your codebase. That doesn't mean you shouldn't write clean code. Your data governance program will eventually be forgotten by future employees who won't understand why it mattered. That doesn't mean you shouldn't build it.

Fighting entropy isn't about winning. It's about extending the window of meaning. It's about building systems that stay coherent longer than they would have otherwise. It's about making structures that hold, even knowing they won't hold forever.

Why This Matters Now

We're in the middle of an interesting moment.

AI can generate content faster than humans ever could. This is incredible for productivity. It's also an entropy accelerator. More data. More documents. More code. More dashboards. All generated instantly, with no maintenance plan.

The bottleneck is no longer creation. It's curation. It's knowing what's true.

An organization that generates ten thousand AI-written documents per week without any system for maintaining their accuracy has an entropy problem, not a productivity gain. They've traded signal for noise.

The companies that will matter in ten years aren't the ones generating the most content. They're the ones maintaining the most coherence. They're the ones who figured out how to fight entropy at scale.

The Work

I write Against Entropy because I believe the work matters.

Not the sexy work of building new AI models or launching new startups or announcing new features. The mundane work of maintaining meaning. Of defining terms. Of governing data. Of writing documentation that future engineers will actually read.

Engineers are artists who often don't know it. We compose systems the way composers arrange sound. We make choices about elegance, tension, resolution. The best code has rhythm. The best architectures have a point of view.

And like all artists, we're fighting entropy. Trying to impose temporary order on a universe that trends toward disorder. Knowing we won't win forever. Doing it anyway.

That's the newsletter. That's the company. That's the work.

Against Entropy.

This is the kind of thinking I publish in Against Entropy. If you're building data systems and want practical frameworks for problems the vendors won't talk about, subscribe below.

Further Reading

If this topic interests you, here's where to go deeper:

On thermodynamic entropy: Sean Carroll's "From Eternity to Here" is the best popular treatment of entropy, time, and cosmology I've ever read.

On information entropy: James Gleick's "The Information" tells the story of Claude Shannon and the birth of information theory.

On data-centric architecture: Dave McComb's "The Data-Centric Revolution" explains why most enterprise data problems are actually architecture problems.

On semantic drift: My article The Two Ways Your Data Lies to You goes deep on syntactic vs. semantic drift and what to do about it.